Interview with Leah Bobet

An interview with Leah Bobet by Derek Newman-Stille

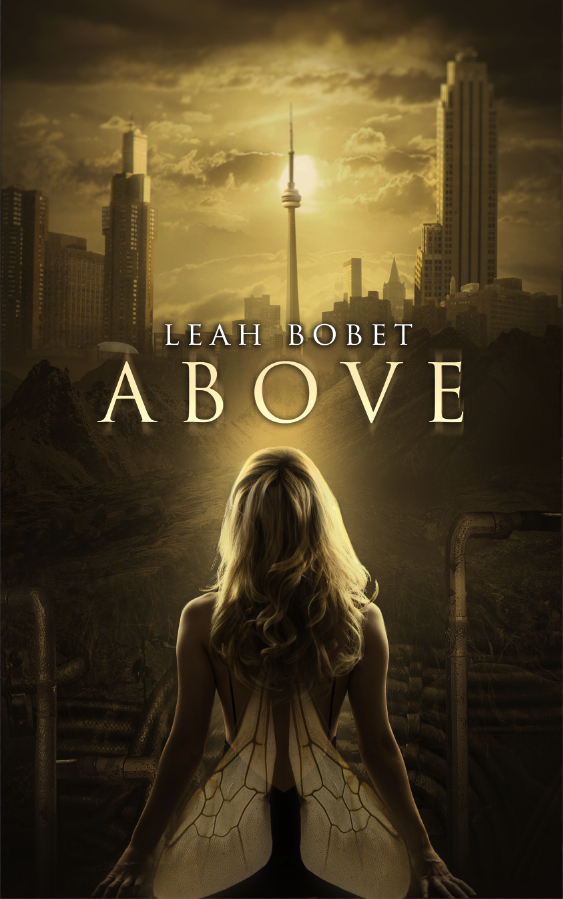

I was fortunate enough to meet Leah Bobet at CAN CON: The Conference on Canadian Content in Speculative Arts and Literature in Ottawa this past year. We had a brief chat about SF and inclusivity, and I got back in touch with her again after reading her novel Above, which I was excited about because it dealt with disability (the focus of my research). I was very excited when Leah Bobet agreed to do an interview here on Speculating Canada so I could share some of her insights with readers.

Spec Can: To begin our interview, could you tell readers a little bit about yourself?

Leah Bobet: Hmm. It’s always a tricky thing to decide what’s interesting about oneself.

I’m a writer and editor, and also work as a bookseller at Bakka-Phoenix Books, Canada’s oldest speculative fiction bookstore. I run Ideomancer Speculative Fiction, a quarterly webzine, and write for Shadow Unit, a project that’s best described as fanfic for a TV show that never existed, alongside Emma Bull, Elizabeth Bear, Will Shetterly, Amanda Downum, Holly Black, and Chelsea Polk.

Before going to full-time writing, though, I worked as a non-partisan staffer at Queen’s Park, and so local politics – and local activism — are something of a passion: I’m on the board of Women in Toronto Politics, a tiny brand-new non-profit that works to help more women access City Hall and build the communities they want to live in, and I’m going to be working on Toronto’s brand new pedestrian advocacy organization. I’m also deeply into urban agriculture and supporting local food, and spend a lot of my summer working with groups that glean downtown fruit trees or plant gardens in public spaces.

Otherwise, I do a lot of reading; I see a lot of small indie bands in smaller spaces; take wandering, exploratory walks; look for the perfect Eggs Benedict; and make bad puns about Captain Jean-Luc Picard.

Spec Can: Above was a novel about discrimination. What types of discrimination were you thinking of when writing this? What social plights influenced this story’s discourse on discrimination?

Leah Bobet: I was thinking, mostly, about intersectionality: How we can be legitimately marginalized because of one aspect of who we are, and legitimately marginalizing someone else because of another facet. Every single character in the book has that dual role, because that’s life; that’s how people are and can be.

Some of that comes out of my own background. I grew up in a minority culture, PTSD everyone-will-genocide-you tics and all, but in such a homogenous neighbourhood that I never really felt that social difference until I was an adult with a strong sense of my own power. It was a slightly weird way to grow up, and made cultural politics both complicated and fascinating: People I cared about acted in ways that to my mind were horrifying, racist, and amoral, but to them were self-defense, because having been victimized so badly meant whatever steps you took were justified. And there was no communicating one side to the other. The context gap was just too great.

So I wanted to talk about that: the damage that our damage does, and how on earth one strikes a balance between recognizing what one’s suffered and perpetuating it on someone else.

One of the other focuses was disability: both physical disability and mental illness. And that came about partially because of my own dissatisfaction with the official line on mental illness, and because of a friend, who’s mobility-impaired, speaking about how stories about kids in wheelchairs always had them sidelined as assistants to the nice, smiling, able heroes. So one of the goals I had for Above was to write a story where disabled people were the heroes and the able people got to die tragically for their cause. It felt like a thing worth doing, and it turned out that it was.

Spec Can: What role can Speculative Fiction have in helping people to question their biases?

Leah Bobet: There is a stock reply to this question: about metaphor, and removing present concerns from their context to sneakily teach people lessons from other angles. Rocketship angles! With space morals! But it’s not an answer I tend to believe in, and not one I can really give.

I think the role of speculative fiction in confronting bias depends very strongly on the reader, the book, and whether they’re ready for each other on the day they meet.

Books have made me question my biases and move past them, or never develop certain noxious ones. In fact, the best reviews I’ve heard for Above were the ones where people said, “This made me want to do something.” But that doesn’t fool me into thinking speculative fiction has some sort of special magic that readers of other genres – or TV-watchers, or gamers – will never access. That’s, ironically, a bias that speculative fiction readers have – one that feeds into our ideas of ourselves as more enlightened, better, and smarter, and misses the fact that of course speculative work will reach readers like us better than other kinds. Because otherwise we wouldn’t be reading speculative fiction in the first place. We’d be face-first into a detective book and never pick up SFF to start with – and we’d be having conversations about our biases in the tropes of detective fiction.

Reading, to me, is a dialogue. It’s a conversation between the ideas in the book and the ideas in the reader’s head, and then you see how well they meet in the middle. Sometimes the reader’s not in a place where they’re ready to be receptive to a book’s point. Sometimes what the book’s saying is just old news to that reader (good example: I tend to appreciate early feminist SFF, but a lot of it feels like someone trying to convince me the sky is blue. Generational context. Go figure.) Sometimes book and reader just legitimately disagree. And that’s true of all novels, all genres, and all forms of telling people a story – speculative or not. The only thing we can really do, as readers, is read widely and with open minds.

Spec Can: Your novel Above brings critical attention to scientists and, particularly to medical practitioners (the Whitecoats in the novel). What questions were you hoping your readers would ask about medical practices and the cultural ideas underlying them?

Leah Bobet: Actually, in terms of the Whitecoats and Dr. Marybeth’s balancing role, I was hoping people would treat that question of medical practices thoughtfully – just like everything else in Above – and consider what our treatment of mental illness and disability mean in terms that aren’t black and white.

Like anyone else, the medical practitioners in Above are people: a mixture of good and bad personalities and ideas. And like everything else, who’s good or bad depends on who’s telling the story. The type of person who would prefer to live in a roughed-out underground cavern rather than in bad circumstances that still include heating and flush toilets just…they didn’t seem like they’d have kind things to say about the medical profession. And so Safe has the concept of Whitecoats. And that’s less about me getting a particular message across than trying to create those characters logically, and build a culture that was true to how they’d feel – and then explore the consequences of that culture on their children.

Spec Can: Above focusses on the narration of Matthew, the Teller for the community called “Safe”. His role is primarily to tell stories of the community. What role do you see stories having in creating a community? How can the telling of the past form a sense of shared history?

Leah Bobet: I think stories basically are the defining factor of a community. Identity’s a funny thing: We tell stories about ourselves (and others, and that’s where we get stereotyping), and when we compare those stories and they come up the same, we decide we’re the same. Community is shared stories. Community splinters when our worldviews – the stories we tell about the world – get too far apart.

There are about a trillion examples of how giving people a narrative binds them together – the most obvious one being the US, where the patriotism story is so frequently hammered home and so prominent because (I think, sometimes) it’s so big and full of people who have nothing in common, period. That’s looking back to shared history every day: We did something together, we shared experience and values, and so we must be the same. It’s functionally a social hack. And it can really work to smooth out the tensions caused by present differences, until it doesn’t.

This is, in some ways, a very academic-linguistic perspective on communities, and how and why we form them (sorry; I trained as a linguist, and it’s in everything I do). The warmer, more optimistic side of that, though: It gives us the option of making our own communities. We can get together, with our shared experiences, and be social and understood and not be alone. And that’s kind of a wonderful gift for those of us who don’t fit well into the places we were born, and need to make new places; who need to make Safe.

Spec Can: In Above, the characters also raise the issue of history that is edited out, stories that are deleted and not spoken of. Canada has a bad history of removing people’s stories to benefit its own image. What stories do you feel we, as a society, are ignoring?

Leah Bobet: The stories I was thinking of when I wrote Above were First Nations stories; the loss of language, poverty, colonial barriers, high suicide rates, and general slow genocide going on in our cozy little first-world country. I was taking some classes that threw light onto those issues at the time: one on First Nations languages and language revitalization, and one on First Nations women’s modern literature. The Idle No More movement has brought a lot more attention to those stories in the last few months, and I’m really hoping it doesn’t die in the next news cycle. It’s too wrong, and it needs too much discussion, action, and righting.

But I was thinking about revisionist history in general: in relationships, in families as well as in nations. Many people have stories they just don’t tell, even to themselves. It’s always worth asking why.

As for stories we’re currently ignoring: I’m afraid I’m not the best person to ask. I’m aware that I live with a certain amount of advantages in my life, and that all kinds of things go on – experiences, injustices, needs, fears, loves – that I don’t see because of where and how I live. It’d be a better thing, I think, if we all talked to each other a little bit more; talked to people who are living poverty, disability, mental illness, racism, sexism, transphobia, and everything else – instead of asking the people who write about them. We don’t and shouldn’t need spokespeople that way. We should respect each other’s voices.

Spec Can: Trauma plays an important part in Above in the background of your characters and is important in forming their identities. Why is trauma such an essential part of this book?

Leah Bobet: Trauma’s a big player in Above mostly because of what I was interested in exploring: What we do to each other out of our own trauma, and where the limits of making room for trauma bump up against treating other people terribly. The discourse on trauma in North American society is…well, it’s reasonably new, and so maybe a bit awful. There’s not a lot of room between Walk it off! and treating trauma as a debilitating, central tragedy of one’s life; one that excuses everything after. And like most binaries, there’s a lot of discussion to be had about the experiences that live in the middle.

Spec Can: What can Speculative Fiction do that “Realist” fiction can’t?

Leah Bobet: Nothing. What a work of fiction can do depends on the author, the ideas, and how they use their tools.

Spec Can: Is there something distinctive about Canadian SF?

Leah Bobet: That’s, again, quite hard for me to say. Each individual author’s such a unique mix of their own influences, interests, and passions that I don’t know if the idea of national literatures can stay as it traditionally has: some notion of a geographical “character” that influences the stories we tell. Or some trait, like a genetic marker, that everyone we label as Canadian SF will have.

A few questions up, we talked about stories as community, and forming communities of choice instead of birth or geography. I think this might be an outgrowth of that ability: My friend who really identifies with Japanese shoujo tropes can write her Japanese-influenced near-future literary fiction. I can write my magical realist social justice and urban planning stories, with bonus! ruins and city gardening. We live in the same city. We’ve just gravitated to the stories that resonate with who we are, instead of telling stories and using tropes that are bounded by the place we were born.

Spec Can: Is there anything distinctly Canadian about the characters and settings you create?

Leah Bobet: Well, they are Canadian. That’s pretty much it: anything I consider a marker of Canadian literature in my own work – multicultural casts, quieter and smaller stories, that fixation with landscape as character – I’ve seen in works from other countries too, and it’s a somewhat narrow view of what Canadian fiction is and can do.

I’ve written characters and settings that were American, but I prefer to keep my stories above the border, just because this is home; it’s where my heart is.

Spec Can: What was it like to write about an intersexed character? What inspired you to write about an intersexed person?

Leah Bobet: It was on one level an intensely tricky experience – checking one’s assumptions and shorthands every step of the way, and I’m certain I still failed hir in a number of respects. But on another level, it was like writing any other character, because sie’s…just a person: one who lives, loves, hates, chooses, and makes some intensely bad decisions for reasons that are not entirely hir own fault. I made sure I wasn’t writing An Intersex Character™; that I was writing that person instead, at all times.

As for the inspiration: A friend of mine is a doctor, and back in her residency blogged privately about that experience, including delivering and dealing with the system around intersex children. It stuck as something intensely painful and unfair, to the children and families both. And so when I went to write a story about discrimination, the stories my friend told – and the issues around sex assignment within a week of birth – were at the top of my list to include.

Spec Can: What drew you to write Young Adult books? What can Speculative Fiction do for young people?

Leah Bobet: Me writing young adult books actually happened entirely by accident! When I wrote Above, it was in my mind an adult novel. It was only in having my agent point out that there was a coming-of-age arc, as well as a young protagonist, in Above that I even entertained the notion that it could be published as YA. I’m writing young adult deliberately now, on my current project, and it’s been a learning curve.

As for speculative fiction aimed at young adults, I don’t really feel like that concept needs to be sold to the public. Most of what young adults read – and always have – has been speculative fiction, for the cold business reason that there have not been, until recently, genre shelves in the YA section of the bookstore. Parents are generally content that young readers are reading, so YA books have always had a little more freedom to remix, blend, and use whatever genres they feel like. It’s only when we reach the adult sections of the bookstore that anyone cares to get into slapfights about whose genre can beat up whose.

Spec Can: How can Speculative Fiction authors bring more diversity into their work?

Leah Bobet: It’s a funny thing, that: Just do it.

Look at the characters you have in your work and ask how diverse they are. If the answer doesn’t satisfy you, well, think of all the ways people can be diverse in real life, and start getting that in there. Read fiction and non-fiction stories from and about diverse people: people of colour, disabled people, queer people, trans people, people whose religion is different from yours. Think critically about them, and do some informed imagining of what the world’s like from their perspective. When you get evidence that your informed imagining isn’t all there yet, don’t get mad and give up; revise the model to be better and clearer. And then use that model as part of your storytelling kit.

But mostly? Just do it. Because a lot of hand-wringing goes on from writers who don’t feel themselves to be diverse about how on earth they will possibly write diverse fiction. And that hand-wringing can ultimately be a way of putting off the job: of deciding it’s too hard, the same way someone can be “researching” a novel for years and never write a word.

So do it. Commit yourself to thinking and learning. And then do it better next time.

Spec Can: How do ideas of the mythic influence your work? What mythologies speak to you?

Leah Bobet: Subtly, I think. I was a little nuts for the mythic when I was a kid – mostly Greek, Roman, and Inuit stories – because my childhood culture didn’t have a great sense of magic, and I wanted magic very badly. These days, though, there’s no separating the stories from the people; I’m a little too aware that “myth” is a word we use to describe dead cultural stories we’ve decided aren’t true, and I’m leery of it. It’s a little too much like talking smack about someone else’s family.

I’m most interested – and probably because of that unbreakable association of mythic stories with the people whose stories those are, to whom they’re precious – in writing work that explores how people interface with those stories. What do they mean to someone? What’s the interaction this person has between their here-and-now concerns and the ineffable, and how can those things be made to balance, if at all? Because they’re living stories, which means people live with them. I’m most curious as to how.

I want to thank Leah Bobet for her incredible insights and for her discussion of the importance of narratives in the development of community. It is always great to interview an author that also works in the realm of advocacy.

You can find out more about Leah Bobet and her current projects on her website at http://leahbobet.com/ .