Interview with Cait Gordon on Disability in Science fiction, Humour, and Space Opera

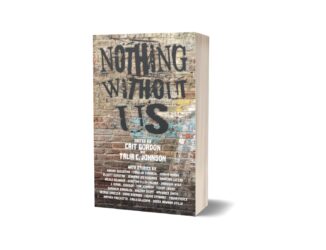

In this episode of Speculating Canada, I interview Cait Gordon, editor of Nothing Without Us and Nothing Without Us Too and author of Iris and The Crew Tear Through Space, Life In the ‘Cosm, and The Stealth Lovers. We explore disability in science fiction, the need for disabled stories, space opera, and humour fiction. Cait wants to remind the audience...